Chapter 20: Deploying Django

Throughout this book, weve mentioned a number of goals that drive the development of Django. Ease of use, friendliness to new programmers, abstraction of repetitive tasks these all drive Djangos developers.

However, since Djangos inception, theres always been another important goal: Django should be easy to deploy, and it should make serving large amounts of traffic possible with limited resources.

The motivations for this goal are apparent when you look at Djangos background: a small, family-owned newspaper in Kansas can hardly afford top-of-the-line server hardware, so Djangos original developers were concerned with squeezing the best possible performance out of limited resources. Indeed, for years Djangos developers acted as their own system administrators there simply wasnt enough hardware to need dedicated sysadmins even as their sites handled tens of millions of hits a day.

As Django became an open source project, this focus on performance and ease of deployment became important for a different reason: hobbyist developers have the same requirements. Individuals who want to use Django are pleased to learn they can host a small- to medium-traffic site for as little as $10 a month.

But being able to scale down is only half the battle. Django also needs to be capable of scaling up to meet the needs of large companies and corporations. Here, Django adopts a philosophy common among LAMP-like Web stacks often called shared nothing .

Whats LAMP?

The acronym LAMP was originally coined to describe a popular set of open source software used to drive many Web sites:

Linux (operating system)

Apache (Web server)

MySQL (database)

PHP (programming language)

Over time, though, the acronym has come to refer more to the philosophy of these types of open source software stacks than to any one particular stack. So while Django uses Python and is database-agnostic, the philosophies proven by the LAMP stack permeate Djangos deployment mentality.

There have been a few (mostly humorous) attempts at coining a similar acronym to describe Djangos technology stack. The authors of this book are fond of LAPD (Linux, Apache, PostgreSQL, and Django) or PAID (PostgreSQL, Apache, Internet, and Django). Use Django and get PAID!

A Note on Personal Preferences

Before we get into the details, a quick aside.

Open source is famous for its so-called religious wars; much (digital) ink has been spilled arguing over text editors (emacs vs. vi ), operating systems (Linux vs. Windows vs. Mac OS), database engines (MySQL vs. PostgreSQL), and of course programming languages.

We try to stay away from these battles. There just isnt enough time.

However, there are a number of choices when it comes to deploying Django, and were constantly asked for our preferences. Since stating these preferences comes dangerously close to firing a salvo in one of the aforementioned battles, weve mostly refrained. However, for the sake of completeness and full disclosure, well state them here. We prefer the following:

Linux (Ubuntu, specifically) as our operating system

Apache and mod_python for the Web server

PostgreSQL as a database server

Of course, we can point to many Django users who have made other choices with great success.

Using Django with Apache and mod_python

Apache with mod_python currently is the most robust setup for using Django on a production server.

mod_python (http://www.djangoproject.com/r/mod_python/) is an Apache plug-in that embeds Python within Apache and loads Python code into memory when the server starts. Code stays in memory throughout the life of an Apache process, which leads to significant performance gains over other server arrangements.

Django requires Apache 2.x and mod_python 3.x, and we prefer Apaches prefork MPM, as opposed to the worker MPM.

Note

Configuring Apache is well beyond the scope of this book, so well simply mention details as needed. Luckily, a number of great resources are available if you need to learn more about Apache. A few of them we like are as follows:

The free online Apache documentation, available via http://www.djangoproject.com/r/apache/docs/

Pro Apache, Third Edition (Apress, 2004) by Peter Wainwright, available via http://www.djangoproject.com/r/books/pro-apache/

Apache: The Definitive Guide, Third Edition (OReilly, 2002) by Ben Laurie and Peter Laurie, available via http://www.djangoproject.com/r/books/apache-pra/

Basic Configuration

To configure Django with mod_python, first make sure you have Apache installed with the mod_python module activated. This usually means having a LoadModule directive in your Apache configuration file. It will look something like this:

LoadModule python_module /usr/lib/apache2/modules/mod_python.so

Then, edit your Apache configuration file and add the following:

<Location "/">

SetHandler python-program

PythonHandler django.core.handlers.modpython

SetEnv DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE mysite.settings

PythonDebug On

</Location>

Make sure to replace mysite.settings with the appropriate DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE for your site.

This tells Apache, Use mod_python for any URL at or under /, using the Django mod_python handler. It passes the value of DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE so mod_python knows which settings to use.

Note that were using the <Location> directive, not the <Directory> directive. The latter is used for pointing at places on your filesystem, whereas <Location> points at places in the URL structure of a Web site. <Directory> would be meaningless here.

Apache likely runs as a different user than your normal login and may have a different path and sys.path. You may need to tell mod_python how to find your project and Django itself.

PythonPath "['/path/to/project', '/path/to/django'] + sys.path"

You can also add directives such as PythonAutoReload Off for performance. See the mod_python documentation for a full list of options.

Note that you should set PythonDebug Off on a production server. If you leave PythonDebug On , your users will see ugly (and revealing) Python tracebacks if something goes wrong within mod_python.

Restart Apache, and any request to your site (or virtual host if youve put this directive inside a <VirtualHost> block) will be served by Django.

Note

If you deploy Django at a subdirectory that is, somewhere deeper than / Django wont trim the URL prefix off of your URLpatterns. So if your Apache config looks like this:

<Location "/mysite/">

SetHandler python-program

PythonHandler django.core.handlers.modpython

SetEnv DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE mysite.settings

PythonDebug On

</Location>

then all your URL patterns will need to start with "/mysite/" . For this reason we usually recommend deploying Django at the root of your domain or virtual host. Alternatively, you can simply shift your URL configuration down one level by using a shim URLconf:

urlpatterns = patterns('',

(r'^mysite/', include('normal.root.urls')),

)

Running Multiple Django Installations on the Same Apache Instance

Its entirely possible to run multiple Django installations on the same Apache instance. You might want to do this if youre an independent Web developer with multiple clients but only a single server.

To accomplish this, just use VirtualHost like so:

NameVirtualHost *

<VirtualHost *>

ServerName www.example.com

# ...

SetEnv DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE mysite.settings

</VirtualHost>

<VirtualHost *>

ServerName www2.example.com

# ...

SetEnv DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE mysite.other_settings

</VirtualHost>

If you need to put two Django installations within the same VirtualHost , youll need to take a special precaution to ensure mod_pythons code cache doesnt mess things up. Use the PythonInterpreter directive to give different <Location> directives separate interpreters:

<VirtualHost *>

ServerName www.example.com

# ...

<Location "/something">

SetEnv DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE mysite.settings

PythonInterpreter mysite

</Location>

<Location "/otherthing">

SetEnv DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE mysite.other_settings

PythonInterpreter mysite_other

</Location>

</VirtualHost>

The values of PythonInterpreter dont really matter, as long as theyre different between the two Location blocks.

Running a Development Server with mod_python

Because mod_python caches loaded Python code, when deploying Django sites on mod_python youll need to restart Apache each time you make changes to your code. This can be a hassle, so heres a quick trick to avoid it: just add MaxRequestsPerChild 1 to your config file to force Apache to reload everything for each request. But dont do that on a production server, or well revoke your Django privileges.

If youre the type of programmer who debugs using scattered print statements (we are), note that print statements have no effect in mod_python; they dont appear in the Apache log, as you might expect. If you have the need to print debugging information in a mod_python setup, youll probably want to use Pythons standard logging package. More information is available at http://docs.python.org/lib/module-logging.html. Alternatively, you can or add the debugging information to the template of your page.

Serving Django and Media Files from the Same Apache Instance

Django should not be used to serve media files itself; leave that job to whichever Web server you choose. We recommend using a separate Web server (i.e., one thats not also running Django) for serving media. For more information, see the Scaling section.

If, however, you have no option but to serve media files on the same Apache VirtualHost as Django, heres how you can turn off mod_python for a particular part of the site:

<Location "/media/">

SetHandler None

</Location>

Change Location to the root URL of your media files.

You can also use <LocationMatch> to match a regular expression. For example, this sets up Django at the site root but explicitly disables Django for the media subdirectory and any URL that ends with .jpg , .gif , or .png :

<Location "/">

SetHandler python-program

PythonHandler django.core.handlers.modpython

SetEnv DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE mysite.settings

</Location>

<Location "/media/">

SetHandler None

</Location>

<LocationMatch "\.(jpg|gif|png)$">

SetHandler None

</LocationMatch>

In all of these cases, youll need to set the DocumentRoot directive so Apache knows where to find your static files.

Error Handling

When you use Apache/mod_python, errors will be caught by Django in other words, they wont propagate to the Apache level and wont appear in the Apache error_log .

The exception to this is if something is really messed up in your Django setup. In that case, youll see an Internal Server Error page in your browser and the full Python traceback in your Apache error_log file. The error_log traceback is spread over multiple lines. (Yes, this is ugly and rather hard to read, but its how mod_python does things.)

Handling a Segmentation Fault

Sometimes, Apache segfaults when you install Django. When this happens, its almost always one of two causes mostly unrelated to Django itself:

It may be that your Python code is importing the pyexpat module (used for XML parsing), which may conflict with the version embedded in Apache. For full information, see Expat Causing Apache Crash at http://www.djangoproject.com/r/articles/expat-apache-crash/.

It may be because youre running mod_python and mod_php in the same Apache instance, with MySQL as your database back-end. In some cases, this causes a known mod_python issue due to version conflicts in PHP and the Python MySQL back-end. Theres full information in a mod_python FAQ entry, accessible via http://www.djangoproject.com/r/articles/php-modpython-faq/.

If you continue to have problems setting up mod_python, a good thing to do is get a bare-bones mod_python site working, without the Django framework. This is an easy way to isolate mod_python-specific problems. The article Getting mod_python Working details this procedure: http://www.djangoproject.com/r/articles/getting-modpython-working/.

The next step should be to edit your test code and add an import of any Django-specific code youre using your views, your models, your URLconf, your RSS configuration, and so forth. Put these imports in your test handler function and access your test URL in a browser. If this causes a crash, youve confirmed its the importing of Django code that causes the problem. Gradually reduce the set of imports until it stops crashing, so as to find the specific module that causes the problem. Drop down further into modules and look into their imports as necessary. For more help, system tools like ldconfig on Linux, otool on Mac OS, and ListDLLs (from SysInternals) on Windows can help you identify shared dependencies and possible version conflicts.

Using Django with FastCGI

Although Django under Apache and mod_python is the most robust deployment setup, many people use shared hosting, on which FastCGI is the only available deployment option.

Additionally, in some situations, FastCGI allows better security and possibly better performance than mod_python. For small sites, FastCGI can also be more lightweight than Apache.

FastCGI Overview

FastCGI is an efficient way of letting an external application serve pages to a Web server. The Web server delegates the incoming Web requests (via a socket) to FastCGI, which executes the code and passes the response back to the Web server, which, in turn, passes it back to the clients Web browser.

Like mod_python, FastCGI allows code to stay in memory, allowing requests to be served with no startup time. Unlike mod_python, a FastCGI process doesnt run inside the Web server process, but in a separate, persistent process.

Why Run Code in a Separate Process?

The traditional mod_* arrangements in Apache embed various scripting languages (most notably PHP, Python/mod_python, and Perl/mod_perl) inside the process space of your Web server. Although this lowers startup time (because code doesnt have to be read off disk for every request), it comes at the cost of memory use.

Each Apache process gets a copy of the Apache engine, complete with all the features of Apache that Django simply doesnt take advantage of. FastCGI processes, on the other hand, only have the memory overhead of Python and Django.

Due to the nature of FastCGI, its also possible to have processes that run under a different user account than the Web server process. Thats a nice security benefit on shared systems, because it means you can secure your code from other users.

Before you can start using FastCGI with Django, youll need to install flup , a Python library for dealing with FastCGI. Some users have reported stalled pages with older flup versions, so you may want to use the latest SVN version. Get flup at http://www.djangoproject.com/r/flup/.

Running Your FastCGI Server

FastCGI operates on a client/server model, and in most cases youll be starting the FastCGI server process on your own. Your Web server (be it Apache, lighttpd, or otherwise) contacts your Django-FastCGI process only when the server needs a dynamic page to be loaded. Because the daemon is already running with the code in memory, its able to serve the response very quickly.

Note

If youre on a shared hosting system, youll probably be forced to use Web server-managed FastCGI processes. If youre in this situation, you should read the section titled Running Django on a Shared-Hosting Provider with Apache, below.

A Web server can connect to a FastCGI server in one of two ways: it can use either a Unix domain socket (a named pipe on Win32 systems) or a TCP socket. What you choose is a manner of preference; a TCP socket is usually easier due to permissions issues.

To start your server, first change into the directory of your project (wherever your manage.py is), and then run manage.py with the runfcgi command:

./manage.py runfcgi [options]

If you specify help as the only option after runfcgi , a list of all the available options will display.

Youll need to specify either a socket or both host and port . Then, when you set up your Web server, youll just need to point it at the socket or host/port you specified when starting the FastCGI server.

A few examples should help explain this:

Running a threaded server on a TCP port:

./manage.py runfcgi method=threaded host=127.0.0.1 port=3033

Running a preforked server on a Unix domain socket:

./manage.py runfcgi method=prefork socket=/home/user/mysite.sock pidfile=django.pid

Run without daemonizing (backgrounding) the process (good for debugging):

./manage.py runfcgi daemonize=false socket=/tmp/mysite.sock

Stopping the FastCGI Daemon

If you have the process running in the foreground, its easy enough to stop it: simply press Ctrl+C to stop and quit the FastCGI server. However, when youre dealing with background processes, youll need to resort to the Unix kill command.

If you specify the pidfile option to your manage.py runfcgi , you can kill the running FastCGI daemon like this:

kill `cat $PIDFILE`

where $PIDFILE is the pidfile you specified.

To easily restart your FastCGI daemon on Unix, you can use this small shell script:

#!/bin/bash

# Replace these three settings.

PROJDIR="/home/user/myproject"

PIDFILE="$PROJDIR/mysite.pid"

SOCKET="$PROJDIR/mysite.sock"

cd $PROJDIR

if [ -f $PIDFILE ]; then

kill `cat -- $PIDFILE`

rm -f -- $PIDFILE

fi

exec /usr/bin/env - \

PYTHONPATH="../python:.." \

./manage.py runfcgi socket=$SOCKET pidfile=$PIDFILE

Using Django with Apache and FastCGI

To use Django with Apache and FastCGI, youll need Apache installed and configured, with mod_fastcgi installed and enabled. Consult the Apache and mod_fastcgi documentation for instructions: http://www.djangoproject.com/r/mod_fastcgi/.

Once youve completed the setup, point Apache at your Django FastCGI instance by editing the httpd.conf (Apache configuration) file. Youll need to do two things:

Use the FastCGIExternalServer directive to specify the location of your FastCGI server.

Use mod_rewrite to point URLs at FastCGI as appropriate.

Specifying the Location of the FastCGI Server

The FastCGIExternalServer directive tells Apache how to find your FastCGI server. As the FastCGIExternalServer docs (http://www.djangoproject.com/r/mod_fastcgi/FastCGIExternalServer/) explain, you can specify either a socket or a host . Here are examples of both:

# Connect to FastCGI via a socket/named pipe: FastCGIExternalServer /home/user/public_html/mysite.fcgi -socket /home/user/mysite.sock # Connect to FastCGI via a TCP host/port: FastCGIExternalServer /home/user/public_html/mysite.fcgi -host 127.0.0.1:3033

In either case, the the directory /home/user/public_html/ should exist, though the file /home/user/public_html/mysite.fcgi doesnt actually have to exist. Its just a URL used by the Web server internally a hook for signifying which requests at a URL should be handled by FastCGI. (More on this in the next section.)

Using mod_rewrite to Point URLs at FastCGI

The second step is telling Apache to use FastCGI for URLs that match a certain pattern. To do this, use the mod_rewrite module and rewrite URLs to mysite.fcgi (or whatever you specified in the FastCGIExternalServer directive, as explained in the previous section).

In this example, we tell Apache to use FastCGI to handle any request that doesnt represent a file on the filesystem and doesnt start with /media/ . This is probably the most common case, if youre using Djangos admin site:

<VirtualHost 12.34.56.78>

ServerName example.com

DocumentRoot /home/user/public_html

Alias /media /home/user/python/django/contrib/admin/media

RewriteEngine On

RewriteRule ^/(media.*)$ /$1 [QSA,L]

RewriteCond %{REQUEST_FILENAME} !-f

RewriteRule ^/(.*)$ /mysite.fcgi/$1 [QSA,L]

</VirtualHost>

FastCGI and lighttpd

lighttpd (http://www.djangoproject.com/r/lighttpd/) is a lightweight Web server commonly used for serving static files. It supports FastCGI natively and thus is also an ideal choice for serving both static and dynamic pages, if your site doesnt have any Apache-specific needs.

Make sure mod_fastcgi is in your modules list, somewhere after mod_rewrite and mod_access , but not after mod_accesslog . Youll probably want mod_alias as well, for serving admin media.

Add the following to your lighttpd config file:

server.document-root = "/home/user/public_html"

fastcgi.server = (

"/mysite.fcgi" => (

"main" => (

# Use host / port instead of socket for TCP fastcgi

# "host" => "127.0.0.1",

# "port" => 3033,

"socket" => "/home/user/mysite.sock",

"check-local" => "disable",

)

),

)

alias.url = (

"/media/" => "/home/user/django/contrib/admin/media/",

)

url.rewrite-once = (

"^(/media.*)$" => "$1",

"^/favicon\.ico$" => "/media/favicon.ico",

"^(/.*)$" => "/mysite.fcgi$1",

)

Running Multiple Django Sites on One lighttpd Instance

lighttpd lets you use conditional configuration to allow configuration to be customized per host. To specify multiple FastCGI sites, just add a conditional block around your FastCGI config for each site:

# If the hostname is 'www.example1.com'...

$HTTP["host"] == "www.example1.com" {

server.document-root = "/foo/site1"

fastcgi.server = (

...

)

...

}

# If the hostname is 'www.example2.com'...

$HTTP["host"] == "www.example2.com" {

server.document-root = "/foo/site2"

fastcgi.server = (

...

)

...

}

You can also run multiple Django installations on the same site simply by specifying multiple entries in the fastcgi.server directive. Add one FastCGI host for each.

Scaling

Now that you know how to get Django running on a single server, lets look at how you can scale out a Django installation. This section walks through how a site might scale from a single server to a large-scale cluster that could serve millions of hits an hour.

Its important to note, however, that nearly every large site is large in different ways, so scaling is anything but a one-size-fits-all operation. The following coverage should suffice to show the general principle, and whenever possible well try to point out where different choices could be made.

First off, well make a pretty big assumption and exclusively talk about scaling under Apache and mod_python. Though we know of a number of successful medium- to large-scale FastCGI deployments, were much more familiar with Apache.

Running on a Single Server

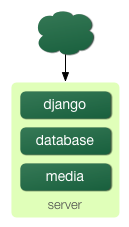

Most sites start out running on a single server, with an architecture that looks something like Figure 20-1.

Figure 20-1: a single server Django setup.

This works just fine for small- to medium-sized sites, and its relatively cheap you can put together a single-server site designed for Django for well under $3,000.

However, as traffic increases youll quickly run into resource contention between the different pieces of software. Database servers and Web servers love to have the entire server to themselves, so when run on the same server they often end up fighting over the same resources (RAM, CPU) that theyd prefer to monopolize.

This is solved easily by moving the database server to a second machine, as explained in the following section.

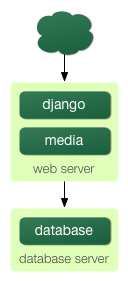

Separating Out the Database Server

As far as Django is concerned, the process of separating out the database server is extremely easy: youll simply need to change the DATABASE_HOST setting to the IP or DNS name of your database server. Its probably a good idea to use the IP if at all possible, as relying on DNS for the connection between your Web server and database server isnt recommended.

With a separate database server, our architecture now looks like Figure 20-2.

Figure 20-2: Moving the database onto a dedicated server.

Here were starting to move into whats usually called n-tier architecture. Dont be scared by the buzzword it just refers to the fact that different tiers of the Web stack get separated out onto different physical machines.

At this point, if you anticipate ever needing to grow beyond a single database server, its probably a good idea to start thinking about connection pooling and/or database replication. Unfortunately, theres not nearly enough space to do those topics justice in this book, so youll need to consult your databases documentation and/or community for more information.

Running a Separate Media Server

We still have a big problem left over from the single-server setup: the serving of media from the same box that handles dynamic content.

Those two activities perform best under different circumstances, and by smashing them together on the same box you end up with neither performing particularly well. So the next step is to separate out the media that is, anything not generated by a Django view onto a dedicated server (see Figure 20-3).

Figure 20-3: Separating out the media server.

Ideally, this media server should run a stripped-down Web server optimized for static media delivery. lighttpd and tux (http://www.djangoproject.com/r/tux/) are both excellent choices here, but a heavily stripped down Apache could work, too.

For sites heavy in static content (photos, videos, etc.), moving to a separate media server is doubly important and should likely be the first step in scaling up.

This step can be slightly tricky, however. Djangos admin needs to be able to write uploaded media to the media server (the MEDIA_ROOT setting controls where this media is written). If media lives on another server, however, youll need to arrange a way for that write to happen across the network.

The easiest way to do this is to use NFS to mount the media servers media directories onto the Web server(s). If you mount them in the same location pointed to by MEDIA_ROOT , media uploading will Just Work.

Implementing Load Balancing and Redundancy

At this point, weve broken things down as much as possible. This three-server setup should handle a very large amount of traffic we served around 10 million hits a day from an architecture of this sort so if you grow further, youll need to start adding redundancy.

This is a good thing, actually. One glance at Figure 20-3 shows you that if even a single one of your three servers fails, youll bring down your entire site. So as you add redundant servers, not only do you increase capacity, but you also increase reliability.

For the sake of this example, lets assume that the Web server hits capacity first. Its easy to get multiple copies of a Django site running on different hardware just copy all the code onto multiple machines, and start Apache on both of them.

However, youll need another piece of software to distribute traffic over your multiple servers: a load balancer . You can buy expensive and proprietary hardware load balancers, but there are a few high-quality open source software load balancers out there.

Apaches mod_proxy is one option, but weve found Perlbal (http://www.djangoproject.com/r/perlbal/) to be simply fantastic. Its a load balancer and reverse proxy written by the same folks who wrote memcached (see Chapter 13).

Note

If youre using FastCGI, you can accomplish this same distribution/load balancing step by separating your front-end Web servers and back-end FastCGI processes onto different machines. The front-end server essentially becomes the load balancer, and the back-end FastCGI processes replace the Apache/mod_python/Django servers.

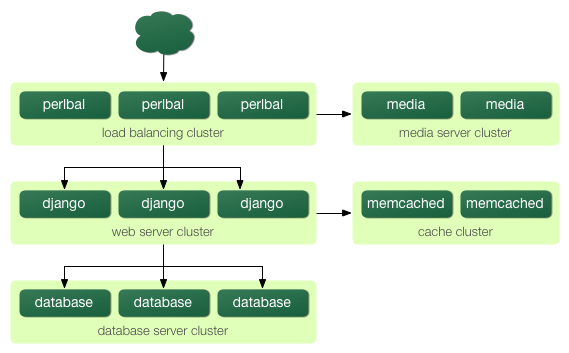

With the Web servers now clustered, our evolving architecture starts to look more complex, as shown in Figure 20-4.

Figure 20-4: A load-balanced, redundant server setup.

Notice that in the diagram the Web servers are referred to as a cluster to indicate that the number of servers is basically variable. Once you have a load balancer out front, you can easily add and remove back-end Web servers without a second of downtime.

Going Big

At this point, the next few steps are pretty much derivatives of the last one:

As you need more database performance, youll need to add replicated database servers. MySQL includes built-in replication; PostgreSQL users should look into Slony (http://www.djangoproject.com/r/slony/) and pgpool (http://www.djangoproject.com/r/pgpool/) for replication and connection pooling, respectively.

If the single load balancer isnt enough, you can add more load balancer machines out front and distribute among them using round-robin DNS.

If a single media server doesnt suffice, you can add more media servers and distribute the load with your load-balancing cluster.

If you need more cache storage, you can add dedicated cache servers.

At any stage, if a cluster isnt performing well, you can add more servers to the cluster.

After a few of these iterations, a large-scale architecture might look like Figure 20-5.

Figure 20-5. An example large-scale Django setup.

Though weve shown only two or three servers at each level, theres no fundamental limit to how many you can add.

Once you get up to this level, youve got quite a few options. Appendix A has some information from a few developers responsible for some large-scale Django installations. If youre planning a high-traffic Django site, its worth a read.

Performance Tuning

If you have huge amount of money, you can just keep throwing hardware at scaling problems. For the rest of us, though, performance tuning is a must.

Note

Incidentally, if anyone with monstrous gobs of cash is actually reading this book, please consider a substantial donation to the Django project. We accept uncut diamonds and gold ingots, too.

Unfortunately, performance tuning is much more of an art than a science, and it is even more difficult to write about than scaling. If youre serious about deploying a large-scale Django application, you should spend a great deal of time learning how to tune each piece of your stack.

The following sections, though, present a few Django-specific tuning tips weve discovered over the years.

Theres No Such Thing As Too Much RAM

As of this writing, the really expensive RAM costs only about $200 per gigabyte pennies compared to the time spent tuning elsewhere. Buy as much RAM as you can possibly afford, and then buy a little bit more.

Faster processors wont improve performance all that much; most Web servers spend up to 90% of their time waiting on disk I/O. As soon as you start swapping, performance will just die. Faster disks might help slightly, but theyre much more expensive than RAM, such that it doesnt really matter.

If you have multiple servers, the first place to put your RAM is in the database server. If you can afford it, get enough RAM to get fit your entire database into memory. This shouldnt be too hard. LJWorld.coms database including over half a million newspaper articles dating back to 1989 is under 2GB.

Next, max out the RAM on your Web server. The ideal situation is one where neither server swaps ever. If you get to that point, you should be able to withstand most normal traffic.

Turn Off Keep-Alive

Keep-Alive is a feature of HTTP that allows multiple HTTP requests to be served over a single TCP connection, avoiding the TCP setup/teardown overhead.

This looks good at first glance, but it can kill the performance of a Django site. If youre properly serving media from a separate server, each user browsing your site will only request a page from your Django server every ten seconds or so. This leaves HTTP servers waiting around for the next keep-alive request, and an idle HTTP server just consumes RAM that an active one should be using.

Use memcached

Although Django supports a number of different cache back-ends, none of them even come close to being as fast as memcached. If you have a high-traffic site, dont even bother with the other back-ends go straight to memcached.

Use memcached Often

Of course, selecting memcached does you no good if you dont actually use it. Chapter 13 is your best friend here: learn how to use Djangos cache framework, and use it everywhere possible. Aggressive, preemptive caching is usually the only thing that will keep a site up under major traffic.

Join the Conversation

Each piece of the Django stack from Linux to Apache to PostgreSQL or MySQL has an awesome community behind it. If you really want to get that last 1% out of your servers, join the open source communities behind your software and ask for help. Most free-software community members will be happy to help.

And also be sure to join the Django community. Your humble authors are only two members of an incredibly active, growing group of Django developers. Our community has a huge amount of collective experience to offer.

Whats Next?

Youve reached the end of our regularly scheduled program. The following appendixes all contain reference material that you might need as you work on your Django projects.

We wish you the best of luck in running your Django site, whether its a little toy for you and a few friends, or the next Google.

е…ідәҺжң¬иҜ„жіЁзі»з»ҹ

жң¬з«ҷдҪҝз”ЁдёҠдёӢж–Үе…іиҒ”зҡ„иҜ„жіЁзі»з»ҹжқҘ收йӣҶеҸҚйҰҲдҝЎжҒҜгҖӮдёҚеҗҢдәҺдёҖиҲ¬еҜ№ж•ҙз« еҒҡиҜ„жіЁзҡ„еҒҡжі•пјҢ жҲ‘们е…Ғи®ёдҪ еҜ№жҜҸдёҖдёӘзӢ¬з«Ӣзҡ„вҖңж–Үжң¬еқ—вҖқеҒҡиҜ„жіЁгҖӮдёҖдёӘвҖңж–Үжң¬еқ—вҖқзңӢиө·жқҘжҳҜиҝҷж ·зҡ„пјҡ

дёҖдёӘвҖңж–Үжң¬еқ—вҖқжҳҜдёҖдёӘж®өиҗҪпјҢдёҖдёӘеҲ—иЎЁйЎ№пјҢдёҖж®өд»Јз ҒпјҢжҲ–иҖ…е…¶д»–дёҖе°Ҹж®өеҶ…е®№гҖӮ дҪ йҖүдёӯе®ғдјҡй«ҳдә®еәҰжҳҫзӨә:

иҰҒеҜ№ж–Үжң¬еқ—еҒҡиҜ„жіЁпјҢдҪ еҸӘйңҖиҰҒзӮ№еҮ»е®ғж—Ғиҫ№зҡ„ж ҮиҜҶеқ—:

жҲ‘们дјҡд»”з»Ҷйҳ…иҜ»жҜҸдёӘиҜ„и®әпјҢеҰӮжһңеҸҜиғҪзҡ„иҜқжҲ‘们д№ҹдјҡжҠҠиҜ„жіЁиҖғиҷ‘еҲ°жңӘжқҘзҡ„зүҲжң¬дёӯеҺ»:

еҰӮжһңдҪ ж„ҝж„ҸдҪ зҡ„иҜ„жіЁиў«йҮҮз”ЁпјҢиҜ·зЎ®дҝқз•ҷдёӢдҪ зҡ„е…ЁеҗҚ (жіЁж„ҸдёҚжҳҜжҳөз§°жҲ–з®Җз§°пјү

Many, many thanks to Jack Slocum; the inspiration and much of the code for the comment system comes from Jack's blog, and this site couldn't have been built without his wonderful

YAHOO.extlibrary. Thanks also to Yahoo for YUI itself.